|

Early Alert? Report

for School Name *Hypothetical Data

Counselor/Administrator Report

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

A. Introduction |

|

| |

|

In the pages that follow, we will report the scores of your students and compare them to other high school students, highlighting groups, individuals and areas that need improvement. This "early alert" program should give you insights to improve your retention of students at risk. In the following report, we will answer nine critical questions related to retention and the improvement of student grades. The answer to these questions is based on your SMART GRADES.NET? scores.

For years we have been successful in recruiting diverse populations, but we paid less attention to keeping these students until graduation. With Early Alert?, retention starts the first day of college, or before. Utilizing SMART GRADES.NET? scores, the institution discovers its areas of strengths and weaknesses in terms of soft skill education. Further, the individual student is able to pinpoint where he/she is strong or needs improvement in eight aptitudes that lead to success. Along with analyses, interventions are offered so students can increase their foundational aptitudes.

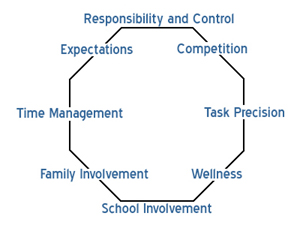

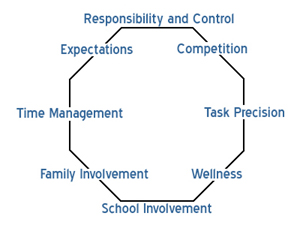

Eight soft skills measured in SMART GRADES.NET? have been empirically shown over 20 years of research to correlate with GPA success, and are represented in the Octagon Learning System?. These factors are:

| Responsibility/Control |

|

Family Involvement |

| Competition/Collaboration |

|

College Involvement |

| Task Precision |

|

Time Management |

| Expectations |

|

Wellness |

(A more complete set of definitions appears in Appendix I of this report.)

What is Academic Success?

The purpose of this report is to promote a successful experience in high school by having students understand and improve their soft skills in what we call "academic success." We have selected eight values represented in SMART GRADES.NET?, which one needs not only to understand, but develop. These values are an important part of academic success, and are empirically related to G.P.A. success in college. They are learned from teachers, parents, peers, academic courses as well as life experiences.

What do we mean by academic success? Academic success may be defined as a foundational set of values, characteristics, both innate and learned, which allow students to complete tasks, learn certain skills, or discern other values. Academic success may be enhanced, forgotten, or never really used. The important thing is that it can always be improved.

When a student writes a successful term paper, it obviously enhances the final grade he receives from the class. But the values, traits, and skills utilized in forming the term paper probably pre-existed the assignment. The ability to organize this assignment and set some time frames for its completion, demonstrate academic aptitude—the foundation for writing a term paper. "At-risk" programs that evaluate a student's course achievement alone often fail to examine preexisting, foundational aspects which create class achievement.

For example, one foundational value is task precision. Students who have a higher aptitude for precision are often the students who check and recheck their math class assignments. Students with an aptitude toward precision are likely to be more concerned about whether or not the quote marks go inside or outside of the period in English composition. In both cases, with higher foundational, academic aptitude for precision, students get higher grades in mathematics and in English. Why? Because the academic aptitude of being precise is demanded by the institution, the subject studied, and in varying degrees by professors/instructors. This is a high-tech culture, and most classes require precision for good grades.

The old adage about catch a fish, feed a boy today—teach him how to fish and feed him for a lifetime, applies here. Each of these eight factors measured in SMART GRADES.NET? prepares the student for successful achievement in a variety of college classes.

A further example may clarify the difference between course content (like algebra) and the fundamentals of learning algebra. If you ask a super bowl coach how he got into the Super Bowl, nine out of ten coaches would say "fundamentals," not how many games they won. The same is true of academic success. Academic aptitude is made up of fundamental factors. If one learns and practices these fundamentals, one will achieve in many courses, and make the dean's list.

Early Alert? Research

SMART GRADES.NET? is an 80-item test measuring academic aptitude for college success. The instrument's reliability (r.90); validity with G.P.A. (r.35 - r.50); and ±50,000-student-norm group are drawn from diverse groups of students throughout the country.

Studies of G.P.A. breakdown and the aptitudes measured show a consistent linear increase in scores grade by grade and corresponding G.P.A.

Further research may be found at www.ombudsmanpress.com/research.htm. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

B. School Name *Hypothetical Data EARLY ALERT? Report ? Academic Year 07/08 - 1st Semester : |

|

| |

|

The Early Alert? Report covers eight areas of academic aptitude scores/comparisons for your students at School Name *Hypothetical Data .

| 1. |

What were the number of students, their gender and their special population designation?

- Number of students in the study 155

- Male / Female n/a

- Special populations n/a

|

| 2. |

How did our total mean score compare with the national norm group?

Your overall mean for 155 students was 310.871 .

Your mean score was 101.925% above the national mean of 305 .

|

| 3. |

How did our mean scores on each of the eight factors of the test compare to the national norm group?

Below you will see the respective factor mean scores, which are the following:

|

Your Mean

Scores |

SMART GRADES.NET?

National Means |

% of

National Means |

| Total Score |

310.871 |

305 |

101.925% |

| Control/Responsibility |

39.568 |

40 |

98.920% |

| Competition |

38.748 |

40 |

96.870% |

| Task Precision |

40.116 |

40 |

100.290% |

| Expectations |

39.303 |

37 |

106.224% |

| Wellness |

36.161 |

36 |

100.447% |

| Time Management |

37.903 |

36 |

105.286% |

| School Involvement |

37.161 |

36 |

103.225% |

| Family Involvement |

41.910 |

40 |

104.775% |

|

| 4. |

What would a charted summary scores profile look like?

Much of our comparison data is based on our "watchline" concept. The watchline for total and subset scores is set at one standard deviation below the national means. We would expect approximately 15% of student scores to be below the watchline.

We believe students with scores below the watchline need an early alert to improve specific scores.

Your combined means scores are represented in the following chart.

|

| 5. |

What were our three highest scores?

From the above scores you will note your students had highest mean scores in the following three key areas:

- Expectations

- Time Management

- Family Involvement

These three high score areas are resulting in higher G.P.A. for your students.

|

| 6. |

What were our three lowest scores and what should we do about them?

- Competition

- Control/Responsibility

- Task Precision

Each of these areas should garner your attention, planning and intervention to improve your students? scores. To help you with this process we have included some improvement definitions, intervention alternatives and checklists for your attention. Select those portions from Appendix III that relate to your three lowest scores.

|

| 7. |

What are your individual student profiles by factor, and which of these needs improvement?

A list of each of your students' scores is presented in Appendix II. You will note each subset score (A-H) representing each factor and that student?s total score in the right-hand column. Please compare student scores in two ways. Student scores below the watchline are noted in red. On the horizontal you will find a set of individual student scores. Second, you may aggregate all scores vertically to more fully understand the total number of student scores below the WATCHLINE for each factor. For example, you might plan to emphasize Time Management in your classes because a high number of your students had scores below the WATCHLINE in Time Management. These two sets of scores, individual (horizontal) and group (vertical), allow you to design and tailor your curriculum interventions. (See Appendix II)

|

| 8. |

Which of our students are at the greatest risk of not returning next year and what can we do to help them return?

The purpose of an "early alert" is to identify high-risk students during 07/08 - 1st Semester , and then apply interventions so larger percentages of these students will return and be successful. With reluctance ? we estimate a large percentage of the following 9 students may not return. We base these estimates on our research of your freshmen students' SMART GRADES.NET? scores.

Student Identification Numbers

We suggest you begin immediate interventions with these 9 students so that they do have a better chance to return next year.

The following names are confidential:

LastName, FirstName

LastName, FirstName

LastName, FirstName

LastName, FirstName

LastName, FirstName

LastName, FirstName

LastName, FirstName

LastName, FirstName

LastName, FirstName

- Have them meet with a counselor/ advisor

- Develop a specific educational plan.

- Arrange specific mentoring experiences with fellow students who are strong in the factors of concern.

- Establish a consistent progress monitoring program.

- Teach a summer bridge program emphasizing factors at risk.

- Retest these students after interventions with SmartGrades.net.

- Organize an academic success class or summer bridge program around the eight factors and follow the 16 week program published in Making the Dean's List.

Our suggested interventions for these students are in our book, Making the Dean's List, in the Cengage series on student success.

|

| 9. |

How does this year's analyses compare to last year related to each of these eight questions above?

In calculating Early Alert?, it is important to compare your scores to those of last year so improvements may be made and trends discovered.

|

|

Report Data

8/3/2007 - 9/21/2007 |

Comparison Data

|

| 1. |

Student Count |

155 |

n/a |

| 2. |

Mean Score |

310.871 |

n/a |

| 3. |

Average Factor Score Control

Competition

Precision

Expectations

Wellness

Time

School

Family |

39.568

38.748

40.116

39.303

36.161

37.903

37.161

41.910

|

n/a

n/a

n/a

n/a

n/a

n/a

n/a

n/a

|

| 5. |

Highest Scores |

- Expectations

- Time Management

- Family Involvement

|

1. n/a

2. n/a

3. n/a |

| 6. |

Lowest Scores |

- Competition

- Control/Responsibility

- Task Precision

|

1. n/a

2. n/a

3. n/a |

| 8. |

Number of High Risk Students |

9 |

n/a |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

We have appreciated the opportunity to assist your students. I will be happy to discuss the results with you.

Sincerely,

Dr. Edmond C. Hallberg

Professor Emeritus

California State University, Los Angeles

President, Ombudsman Press, Inc.

(530) 269-3230

DrEHallberg33@aol.com |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Continued on the next page... |

|

|

Appendix I

Detailed Factor Definitions

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

SMART GRADES.net? Definitions

Academic aptitude may be defined as a set of characteristics, both innate and learned, that allow students to complete tasks, learn certain skills, or discern and apply values. Your academic aptitude may be enhanced, forgotten, or never used, but the important thing we want you to remember is that academic aptitude can be improved.

We are talking about the values and characteristics you must possess before an assignment is ever written or finished. You must be able to organize the assignment, budget time to research the subject, and meet deadlines. These non-writing skills are essential to completing the paper; they are the paper's foundation.

Let us give you another example of an academic aptitude. We know that some students are more precise than others; they take more time revising their assignments, checking their facts, and correcting their answers. You probably have friends or family members whom you would characterize as precise. They are generally the ones who are "neat freaks" about their desks, or who read directions for everything. They may also be more concerned about whether the quote marks go outside the periods in their English assignments. Precision-minded students get higher grades than most of their fellow classmates. Why? Because high school teachers and professors demand precision from their students, regardless of the course or the assignments.

For a better understanding of the elements of SMART GRADES.net?, we have placed the eight factors into an octagon.

Responsibility and Control

Successful students believe that they have a responsibility to learn, so they take control of their education. Often, less successful students believe that their teachers are responsible for educating them, so they place the responsibility and control for their learning away from themselves. Good students look for ways to improve from within; struggling students wait for teachers to tell them what to do.

Successful students believe that hard work and study will be rewarded with good grades. These students feel responsible for earning their grades; this is what we call an "internal locus of control." Unsuccessful students, on the other hand, often believe that their grades are based on "bad luck", "fate", or things teachers "did to them." These students, we say, have an "external locus of control."

Competition

In school, a certain amount of competition is necessary. Successful students compete with others for grades and recognition; they also compete with their own expectations. In group projects, these students collaborate with others to achieve the best grades.

Unsuccessful students tend to have low expectations of themselves and their education; and, therefore, do not compete or collaborate to receive higher grades. Some of these students appear indifferent about their grades.

Task Precision

Successful students finish projects and complete assignments with great attention to detail; they check their facts, their sentences, and their answers thoroughly. They know grades are often assessed on the abilities to follow directions well and eliminate errors; task precision is extremely important in school. Unsuccessful students often leave their assignments half-finished or badly written; ignore facts - or fail to check them; and give careless and sloppy answers.

Expectations

Successful students, with help from parents and others, set their own goals and expectations for their education, their future careers, and their lives. They know what they want, and they go about getting it. Unsuccessful students often have hazy, unspecified ambitions and few expectations of better grades; they are unsure of the purpose of an education. Not knowing what they want, unsuccessful students lack direction, which often impedes their motivation to succeed.

Wellness

Good students care about their health. Many have exercise programs, watch what they eat, and get adequate sleep. They don't drink or take drugs or smoke—they take care of themselves. After all, they need to make sure their health is strong. Keeping their immune system healthy and managing their stress levels are priorities for successful students.

Time Management

Planning, setting and meeting deadlines, and prioritizing assignments—these are all characteristics of successful students. One must arrive at class on time, turn in papers on schedule, and study efficiently; these skills are related to time management, and they directly bear on grades and graduation. Unsuccessful students tend to procrastinate, miss deadlines, study haphazardly, and resist scheduling.

School Involvement

Good students are usually involved in their schools, which means they participate in more than just their classes. They become part of their educational community by joining clubs, sports teams, or student-government councils. Extracurricular activities encourage and improve student success. Some students serve in internships in the community as well.

Family Involvement

Good students enjoy and appreciate their family's support and encouragement. Whether it comes from their parents, their spouses, their children, or significant others, these students understand that such support is an important factor in their success. Students who succeed in school tend to have families who have high expectations.

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Continued on the next page... |

|

|

Appendix II

Individual Student Scores

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

| Student |

Resp |

Comp |

Task |

Exp |

Well |

Time |

School |

Family |

Total |

High Risk |

LastName,

FirstName |

38 |

35 |

28 |

38 |

38 |

25 |

36 |

37 |

275 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

42 |

47 |

39 |

42 |

39 |

36 |

40 |

45 |

330 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

45 |

40 |

41 |

45 |

38 |

42 |

44 |

46 |

341 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

32 |

34 |

36 |

36 |

38 |

29 |

38 |

44 |

287 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

36 |

39 |

42 |

41 |

32 |

42 |

36 |

43 |

311 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

40 |

44 |

41 |

38 |

34 |

37 |

40 |

40 |

314 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

47 |

46 |

49 |

46 |

47 |

49 |

43 |

50 |

377 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

32 |

23 |

31 |

36 |

34 |

40 |

32 |

46 |

274 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

28 |

28 |

30 |

31 |

23 |

28 |

28 |

25 |

221 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

39 |

37 |

32 |

34 |

36 |

34 |

36 |

38 |

286 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

40 |

39 |

42 |

38 |

39 |

37 |

37 |

47 |

319 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

46 |

45 |

50 |

49 |

46 |

48 |

47 |

49 |

380 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

35 |

37 |

38 |

39 |

41 |

38 |

35 |

34 |

297 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

45 |

45 |

46 |

47 |

40 |

44 |

48 |

49 |

364 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

41 |

27 |

42 |

40 |

35 |

46 |

38 |

45 |

314 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

37 |

32 |

38 |

37 |

36 |

44 |

31 |

28 |

283 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

48 |

43 |

44 |

45 |

32 |

49 |

50 |

48 |

359 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

34 |

29 |

35 |

34 |

29 |

40 |

33 |

35 |

269 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

33 |

33 |

37 |

34 |

31 |

33 |

35 |

47 |

283 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

41 |

37 |

38 |

42 |

40 |

41 |

38 |

41 |

318 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Continued on the next page... |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Appendix II - continued |

|

| |

|

| Student |

Resp |

Comp |

Task |

Exp |

Well |

Time |

School |

Family |

Total |

High Risk |

LastName,

FirstName |

36 |

33 |

43 |

38 |

39 |

40 |

31 |

44 |

304 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

50 |

49 |

47 |

45 |

48 |

48 |

37 |

45 |

369 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

38 |

36 |

41 |

39 |

30 |

39 |

27 |

48 |

298 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

36 |

37 |

42 |

40 |

37 |

37 |

35 |

45 |

309 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

42 |

39 |

41 |

37 |

42 |

48 |

39 |

48 |

336 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

41 |

43 |

42 |

42 |

35 |

36 |

39 |

48 |

326 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

47 |

46 |

50 |

43 |

41 |

45 |

45 |

44 |

361 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

50 |

45 |

50 |

46 |

50 |

49 |

50 |

50 |

390 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

41 |

43 |

34 |

39 |

39 |

40 |

33 |

41 |

310 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

47 |

44 |

46 |

43 |

40 |

46 |

44 |

47 |

357 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

42 |

39 |

43 |

45 |

39 |

43 |

47 |

49 |

347 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

44 |

48 |

49 |

45 |

35 |

50 |

42 |

49 |

362 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

34 |

40 |

40 |

39 |

34 |

38 |

30 |

38 |

293 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

41 |

38 |

34 |

38 |

42 |

38 |

26 |

39 |

296 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

43 |

41 |

44 |

43 |

37 |

41 |

39 |

47 |

335 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

45 |

45 |

45 |

46 |

41 |

49 |

41 |

49 |

361 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

43 |

33 |

45 |

41 |

43 |

44 |

33 |

47 |

329 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

43 |

35 |

44 |

40 |

40 |

43 |

43 |

42 |

330 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

41 |

41 |

42 |

41 |

27 |

36 |

31 |

40 |

299 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

27 |

29 |

34 |

34 |

24 |

30 |

38 |

40 |

256 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Continued on the next page... |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Appendix II - continued |

|

| |

|

| Student |

Resp |

Comp |

Task |

Exp |

Well |

Time |

School |

Family |

Total |

High Risk |

LastName,

FirstName |

31 |

29 |

37 |

34 |

31 |

38 |

31 |

45 |

276 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

39 |

37 |

35 |

39 |

34 |

31 |

39 |

46 |

300 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

47 |

41 |

47 |

40 |

38 |

45 |

43 |

46 |

347 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

45 |

48 |

44 |

48 |

39 |

45 |

43 |

48 |

360 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

42 |

36 |

39 |

41 |

33 |

43 |

35 |

42 |

311 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

30 |

37 |

33 |

28 |

31 |

28 |

25 |

42 |

254 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

43 |

37 |

42 |

39 |

40 |

32 |

39 |

46 |

318 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

34 |

28 |

43 |

36 |

19 |

28 |

37 |

46 |

271 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

46 |

38 |

44 |

37 |

38 |

41 |

41 |

46 |

331 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

47 |

46 |

46 |

47 |

39 |

46 |

46 |

44 |

361 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

47 |

45 |

45 |

45 |

42 |

44 |

37 |

41 |

346 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

41 |

40 |

41 |

40 |

38 |

39 |

40 |

44 |

323 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

43 |

45 |

40 |

37 |

37 |

28 |

42 |

50 |

322 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

40 |

41 |

42 |

38 |

35 |

30 |

38 |

44 |

308 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

39 |

41 |

43 |

37 |

38 |

35 |

38 |

45 |

316 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

42 |

38 |

41 |

35 |

29 |

34 |

39 |

36 |

294 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

42 |

28 |

45 |

36 |

28 |

42 |

37 |

47 |

305 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

38 |

41 |

39 |

37 |

29 |

34 |

29 |

37 |

284 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

46 |

43 |

46 |

43 |

36 |

44 |

43 |

48 |

349 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

39 |

42 |

39 |

39 |

39 |

39 |

39 |

40 |

316 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Continued on the next page... |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Appendix II - continued |

|

| |

|

| Student |

Resp |

Comp |

Task |

Exp |

Well |

Time |

School |

Family |

Total |

High Risk |

LastName,

FirstName |

38 |

30 |

41 |

32 |

33 |

36 |

33 |

42 |

285 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

44 |

42 |

47 |

47 |

39 |

46 |

41 |

37 |

343 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

47 |

49 |

48 |

49 |

47 |

46 |

48 |

49 |

383 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

43 |

41 |

41 |

35 |

40 |

33 |

44 |

45 |

322 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

35 |

36 |

34 |

32 |

33 |

33 |

29 |

35 |

267 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

40 |

41 |

40 |

39 |

41 |

40 |

40 |

41 |

322 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

39 |

37 |

43 |

38 |

34 |

37 |

38 |

43 |

309 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

39 |

36 |

38 |

36 |

33 |

37 |

39 |

44 |

302 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

35 |

35 |

39 |

38 |

37 |

30 |

38 |

42 |

294 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

43 |

41 |

44 |

45 |

39 |

44 |

33 |

23 |

312 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

50 |

50 |

49 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

399 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

42 |

44 |

44 |

48 |

45 |

47 |

41 |

48 |

359 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

38 |

35 |

41 |

42 |

36 |

39 |

39 |

44 |

314 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

40 |

41 |

40 |

37 |

25 |

39 |

34 |

42 |

298 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

36 |

36 |

40 |

34 |

35 |

39 |

33 |

40 |

293 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

40 |

23 |

39 |

37 |

34 |

40 |

37 |

37 |

287 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

42 |

38 |

40 |

36 |

35 |

36 |

31 |

46 |

304 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

44 |

34 |

48 |

43 |

39 |

44 |

38 |

46 |

336 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

44 |

42 |

39 |

42 |

42 |

38 |

35 |

43 |

325 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

45 |

47 |

44 |

45 |

40 |

41 |

42 |

19 |

323 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Continued on the next page... |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Appendix II - continued |

|

| |

|

| Student |

Resp |

Comp |

Task |

Exp |

Well |

Time |

School |

Family |

Total |

High Risk |

LastName,

FirstName |

45 |

47 |

43 |

43 |

41 |

38 |

36 |

46 |

339 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

41 |

46 |

40 |

43 |

29 |

38 |

44 |

34 |

315 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

43 |

49 |

40 |

44 |

38 |

39 |

41 |

38 |

332 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

42 |

37 |

41 |

36 |

38 |

37 |

39 |

48 |

318 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

40 |

47 |

43 |

39 |

41 |

41 |

41 |

45 |

337 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

40 |

38 |

39 |

44 |

31 |

39 |

37 |

42 |

310 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

43 |

43 |

46 |

42 |

38 |

45 |

41 |

50 |

348 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

47 |

45 |

42 |

48 |

40 |

44 |

39 |

44 |

349 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

41 |

39 |

44 |

40 |

33 |

42 |

39 |

32 |

310 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

23 |

25 |

25 |

26 |

29 |

28 |

27 |

36 |

219 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

36 |

26 |

34 |

31 |

32 |

39 |

38 |

40 |

276 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

41 |

44 |

40 |

40 |

37 |

40 |

40 |

48 |

330 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

40 |

37 |

40 |

37 |

30 |

41 |

37 |

44 |

306 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

42 |

41 |

42 |

43 |

36 |

40 |

36 |

49 |

329 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

38 |

42 |

39 |

41 |

29 |

31 |

41 |

42 |

303 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

37 |

23 |

38 |

34 |

30 |

35 |

29 |

41 |

267 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

40 |

42 |

36 |

35 |

28 |

33 |

27 |

40 |

281 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

34 |

35 |

38 |

36 |

43 |

35 |

27 |

40 |

288 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

37 |

37 |

42 |

41 |

29 |

31 |

34 |

48 |

299 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

42 |

37 |

44 |

42 |

41 |

36 |

38 |

48 |

328 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Continued on the next page... |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Appendix II - continued |

|

| |

|

| Student |

Resp |

Comp |

Task |

Exp |

Well |

Time |

School |

Family |

Total |

High Risk |

LastName,

FirstName |

49 |

48 |

46 |

45 |

45 |

42 |

40 |

48 |

363 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

42 |

30 |

42 |

40 |

47 |

37 |

32 |

43 |

313 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

40 |

34 |

43 |

37 |

42 |

35 |

29 |

48 |

308 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

43 |

27 |

38 |

37 |

39 |

43 |

33 |

47 |

307 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

37 |

36 |

38 |

40 |

41 |

21 |

36 |

47 |

296 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

38 |

38 |

37 |

39 |

33 |

34 |

35 |

37 |

291 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

41 |

28 |

41 |

35 |

36 |

39 |

40 |

27 |

287 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

33 |

38 |

35 |

37 |

38 |

30 |

34 |

36 |

281 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

41 |

46 |

40 |

38 |

39 |

39 |

37 |

42 |

322 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

36 |

30 |

37 |

27 |

35 |

26 |

24 |

34 |

249 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

43 |

41 |

26 |

43 |

29 |

24 |

31 |

43 |

280 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

30 |

41 |

35 |

33 |

23 |

36 |

40 |

44 |

282 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

39 |

37 |

40 |

39 |

40 |

36 |

39 |

39 |

309 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

41 |

32 |

45 |

40 |

40 |

29 |

27 |

46 |

300 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

38 |

34 |

40 |

35 |

32 |

37 |

37 |

36 |

289 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

39 |

34 |

38 |

41 |

37 |

35 |

39 |

40 |

303 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

35 |

35 |

40 |

37 |

33 |

38 |

35 |

43 |

296 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

41 |

43 |

41 |

44 |

25 |

37 |

32 |

39 |

302 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

37 |

40 |

37 |

37 |

33 |

31 |

40 |

40 |

295 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

37 |

42 |

38 |

44 |

36 |

37 |

41 |

43 |

318 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Continued on the next page... |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Appendix II - continued |

|

| |

|

| Student |

Resp |

Comp |

Task |

Exp |

Well |

Time |

School |

Family |

Total |

High Risk |

LastName,

FirstName |

35 |

38 |

38 |

31 |

35 |

37 |

37 |

34 |

285 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

34 |

39 |

38 |

43 |

32 |

38 |

32 |

42 |

298 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

32 |

37 |

33 |

31 |

38 |

36 |

30 |

36 |

273 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

38 |

43 |

40 |

35 |

35 |

33 |

40 |

45 |

309 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

32 |

44 |

35 |

34 |

30 |

35 |

34 |

37 |

281 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

41 |

41 |

40 |

41 |

34 |

39 |

40 |

41 |

317 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

40 |

41 |

39 |

42 |

40 |

43 |

40 |

48 |

333 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

38 |

40 |

41 |

41 |

40 |

42 |

42 |

28 |

312 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

42 |

40 |

43 |

43 |

33 |

31 |

36 |

37 |

305 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

30 |

45 |

35 |

35 |

36 |

35 |

36 |

41 |

293 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

27 |

29 |

34 |

26 |

30 |

30 |

34 |

28 |

238 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

41 |

44 |

41 |

42 |

35 |

39 |

36 |

45 |

323 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

35 |

46 |

39 |

42 |

42 |

41 |

38 |

42 |

325 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

34 |

30 |

37 |

33 |

33 |

37 |

33 |

41 |

278 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

33 |

32 |

32 |

29 |

31 |

30 |

31 |

32 |

250 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

33 |

39 |

42 |

38 |

36 |

38 |

35 |

38 |

299 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

35 |

38 |

34 |

38 |

27 |

30 |

38 |

39 |

279 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

37 |

40 |

32 |

39 |

28 |

27 |

39 |

37 |

279 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

44 |

41 |

41 |

43 |

43 |

38 |

37 |

42 |

329 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

36 |

39 |

34 |

34 |

30 |

23 |

36 |

44 |

276 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Continued on the next page... |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Appendix II - continued |

|

| |

|

| Student |

Resp |

Comp |

Task |

Exp |

Well |

Time |

School |

Family |

Total |

High Risk |

LastName,

FirstName |

40 |

42 |

36 |

43 |

43 |

42 |

40 |

46 |

332 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

35 |

36 |

38 |

36 |

36 |

33 |

37 |

36 |

287 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

38 |

40 |

37 |

36 |

37 |

33 |

38 |

37 |

296 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

44 |

36 |

44 |

35 |

32 |

36 |

35 |

33 |

295 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

32 |

37 |

39 |

36 |

35 |

38 |

38 |

40 |

295 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

38 |

49 |

39 |

42 |

36 |

40 |

36 |

39 |

319 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

33 |

41 |

35 |

35 |

30 |

33 |

39 |

41 |

287 |

|

LastName,

FirstName |

38 |

43 |

33 |

42 |

38 |

31 |

42 |

46 |

313 |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Continued on the next page... |

|

|

Appendix III

Areas of Improvement

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

The next pages are definitions, contracts and checklists for your students to use in improving your school's lowest 3 scores. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Continued on the next page... |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Competition / Collaboration |

|

| |

|

Introduction

Compared with other factors in SmartGrades.net, competition and collaboration are perhaps the most misunderstood components of the eight academic aptitudes. How can you, as a student, be both competitive and collaborative in school? This is an excellent question, but it sounds like a paradox!

Using the idea of a paradox is helpful for thinking about these two academic aptitudes. A paradox is simply a statement that is seemingly contradictory or opposed to common sense and yet is true. It?s difficult to believe that a person can be competitive and collaborative when the two terms seem contradictory. Yet, it is not only true and possible but also necessary for college success.

SmartGrades.net is used to predict which students are at risk for not returning the second year of college. In one study we conducted, we found that of the 24 students predicted not to return to college, 18 of them scored significantly low on competition. Competition matters.

Sometimes in the world of education the ability to be competitive is not seen as a positive goal. Educators worry about (and rightly so) what will happen to students when competition is overemphasized as a motivation for learning. Must students always have to think in terms of being better or faster or view life as winning or losing, being the best or the worst, or being ahead or behind? Students sometimes feel awkward talking about the issue of competition; they do not want to be seen as overly prideful or contentious. Other students shy away from the topic because they do not view themselves as successful in competitive environments.

In some classes students see competition and collaboration in terms of "either or" and believe that highly competitive students cannot be collaborative and that collaborative students cannot be highly competitive. Simply stated, most individuals see these two characteristics as total opposites. However, both competition and collaboration are necessary for success in college.

The reality is that competition exists everywhere in education. Students compete for grades, scholarships, and spaces at prestigious graduate schools. Faculty compete for promotions, grants, and better teaching schedules. Colleges compete for student enrollment, college ranking, and funding. Today there is even a nationwide discussion on the value of schools competing for students in order to motivate educators to provide a higher quality of education. The issue is not whether competition is part of our academic life but understanding when and where it is appropriate, and realizing that a healthily balanced competitiveness can contribute to your college success.

Collaboration, on the other hand, is viewed in a much more positive light. Collaboration is seen to build skills such as respecting individual contributions to the group, sharing resources, and solving problems collectively. Collaboration requires students to take the major responsibility for the learning process, both in the amount of information and resources needed to answer questions and in how they will evaluate themselves. Some educators consider collaborative learning an excellent model for teaching. Collaboration implies that everyone is an active participant in the learning process so that a sense of community can be created and no student is left behind.

Our experience tells us that students need to learn both competition and collaboration because these skills will be used separately or together all through college life. Each day as a student you deal with competition and collaboration as a paradox. You might participate in intercollegiate sports but strive to be the best player on the team. You compete for an "A" in a course but study in small groups for the exam. You find yourself in competition for a scholarship where there is only one award, and yet you are involved in a collaborative class project where one grade will be assigned to the group.

Successful Students' Aptitudes

Successful students understand the connection between competition and collaboration. They are able to see the value of group projects and working toward a common learning outcome. They believe that learning can occur in a collaborative manner and that sharing resources and information with other students is a positive activity. These students do not try to dominate or overpower class discussions so that other points of view are not expressed. While striving to be an outstanding student, they can work cooperatively and avoid critical and authoritarian behavior.

Successful students also value competition. They have a sense of self-confidence about their abilities, and they learn this because they are engaged in fair and healthy forms of competition. You often find them participating in several competitive activities outside the classroom, such as debate, intercollegiate sports, music, or leadership. Finally, and probably most important, these students do not simply perceive competition as an "I win, you lose" situation. They use their competitive energy for healthy, nondestructive activities. They view competition as a forceful, dynamic, determined, and spirited element of being a successful student. Students who manage competition and collaboration would probably agree with Stephen C. Covey who, in his book The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, speaks of competition as the win/win frame of mind and heart, rather than win/lose.

| |

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Continued on the next page... |

|

|

SMART GRADES?

Students' Responsibility

Checklist and Contract

|

|

|

C O M P E T I T I O N |

|

|

|

|

|

Like to be compared with their own expectations. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Recognize successful students are persuasive. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Understand that students who get good grades are generally considered "active" not "passive." |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Assert their opinions and views. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Like to be in the top 10% of the class. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Develop their own autonomy. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Develop personal expectations. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Be a leader in groups. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Compete in athletics, debates and games. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Associate with other competitive students. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Get some tutoring, if necessary. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Each time you complete one of the items on the checklist, give yourself a check. |

|

|

|

|

|

Student Signature:_____________________________________________ Date:___________ |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Responsibility / Control |

|

| |

|

Introduction

From the rugged pioneers who crossed the plains to the "movers and shakers" and "captains of industry," Americans have always respected independence, autonomy, and control. These are the marks of the successful individual. In college, first-year students are expected to be independent and responsible adults; they must "stand on their own two feet," but many first-year students find this difficult. College creates a struggle between what students perceive the institution wants and what they need. Counselors ask what courses a student wishes to enroll in, but the student often answers by asking, "What should I take?" Eventually, a shift in responsibility and control to the student and away from institutional authority occurs. Successful students realize that they themselves hold the keys to making their college experiences positive and productive.

As students become more responsible, they must plan their careers, budget their college money, and develop relationships with faculty. Coupled with this new set of responsibilities is the establishment of the right amount of control over affairs. This balance is critical for success. Too much responsibility and too little control create stress and the feeling that one is being controlled by external events. Too much control results in stress as well, because people who need too much control always need to be "in charge." Neither case is desired, only a balance between responsibility and control will lead to a manageable stress level. Some individuals view external authority as a controlling factor in life, just as some cultures view "fate" as inescapable. Students holding such views often lack the internal locus of control needed to be the "rugged individualists" that American culture so often celebrates.

Successful Students' Aptitudes

Successful students seem to establish control over their own education and to perform well in the pursuit of superior grades. These students move to the "beat of their own drums" and are in charge of their education instead of their education being in charge of them. They tend to stand up for what they believe. Students who have developed the ability to balance their responsibilities and to gauge the amount of control they need, create lives with more freedom and accomplishments. These students do not depend on others to make their decisions. They may listen to advice and opinions, but they make their final choices and take responsibility for their decisions, regardless of the decisions? outcomes. Successful students do not view their grades as simple results of luck, as things they have no control over.

Students who do well academically and socially in college take responsibility for what they do, even if they are on their own for the first time. These students, little by little, become masters of their academic future. They learn to have attitudes of academic independence, autonomy, and control. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Continued on the next page... |

|

|

SMART GRADES?

Students' Responsibility

Checklist and Contract

|

|

|

R E S P O N S I B I L I T Y / C O N T R O L |

|

|

|

|

|

Take control of their education. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Assist them to stand up for what they believe. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Allow them to grow in control over portions of their out-of-school life. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Develop self-esteem. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Get assignments in on time. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Keep balance between taking on too many responsibilities and having too little control. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Develop their own autonomy. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Be proud of their school work. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Make sure they are assertive about their views. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Have them take initiative in school and not wait for others to tell them what to do. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Develop positive self-talk. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Take responsibility and do not blame others for their poor grades. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Each time you complete one of the items on the checklist, give yourself a check. |

|

|

|

|

|

Student Signature:_____________________________________________ Date:___________ |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Task Precision |

|

| |

|

Introduction

Beginning with registration and ending with commencement, college life is filled with a succession of tasks. When we set goals and achieve them, it is only because we have completed the necessary steps. For example, if you look at the college admissions process, there were a number of steps, done in a timely fashion, that led to your college acceptance. Filling out and mailing applications, getting letters of recommendation, and acquiring achievement scores were a series of tasks you had to complete to achieve your goal of getting into college.

Your acceptance to a certain college was in part determined by the details and the precision you showed when completing the steps, or series of tasks, required for the application process. Regardless of where you chose to attend, the college admissions experience introduced you to what we define and measure in the CSFI as Task Orientation with Precision.

When you think of all the other tasks you had to get out of the way in order to enroll in college, you know that there were many. Even now, your life as a student probably seems to be an endless series of jobs waiting to be done, with many of them requiring precision. While the list may seem incredibly long, we all know that how we complete or fail to complete these and other important tasks affects our jobs, academics, and personal lives.

Our culture values individuals who are completers. We give more credit, and perhaps more than necessary, to those who are doers and not those who just want to be. We want to hire highly productive individuals who can get the job done. "Paying attention to detail" and "staying on task" are phrases we often use in education and work to describe or evaluate students and employees.

Our society can be highly technical, often demanding calculations that are precise to the second or even millisecond. Many people spend their days working in technical jobs that demand a high level of precision and linear sequencing to be accurate. We value individuals who can be precise and use this skill in many services and occupations, for relying on an imprecise mechanic or doctor could have serious consequences.

In college, task orientation with precision is critical. Instructors give grades not only for the ability to complete assignments that demonstrate an understanding of the content but also for precise work that follows specific criteria. For example, work must be handed in on time, be of a specific length or format, and also contain accurate punctuation, spelling, sentence construction, and organization. In math, teachers not only value your understanding of how math problems are solved but also require that these solutions be accomplished precisely, often to the third decimal place. Learning how to complete tasks with the appropriate level of precision will improve not only your grades but also your understanding of your coursework.

Successful Students' Aptitudes

Students who approach assignments with precision achieve higher grades and overall goals. They see themselves as "doers," often successfully involved in many activities. These students know that academic tasks need to be completed within a certain time frame, so they plan accordingly. They are more organized and are able to complete their "to do" lists because they do not procrastinate, which they know will cost them their time to go back and redo. They do not get buried in endless details but use well-developed critical thinking skills to clearly understand which tasks are required to complete the assignments in a thorough and correct manner. They have a sense of accomplishment and pride because they know they are striving for distinction and avoiding mediocrity in their academic endeavors.

| |

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Continued on the next page... |

|

|

SMART GRADES?

Students' Responsibility

Checklist and Contract

|

|

|

T A S K P L A N N I N G / P R E C I S I O N |

|

|

|

|

|

Keep a task list each week. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prioritize task list A, B, C's. A's are the most important. C's are least. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Be precise in speaking, writing and reading. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Learn problem solving techniques. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Form a study group. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dissect assignments before working on them. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Look for details in assignments given. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lay out a task to be accomplished before working on it. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Follow through in a precise manner. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Evaluate why you received the grades you did receive. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Review material studied each week. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Follow assignments step-by-step. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Each time you complete one of the items on the checklist, give yourself a check. |

|

|

|

|

|

Student Signature:_____________________________________________ Date:___________ |

|

|

| |